Australian filmmaker Briony Kidd, co-founder and programmer of Stranger With My Face Horror Film Festival. Image used with permission.

In August this year I was lucky enough to travel to Hobart for the third annual Stranger With My Face Horror Film Festival on behalf of RealTime magazine. An intimate festival with a growing international profile, Stranger With My Face was started in 2012 by Hobart-based filmmakers Rebecca Thomson and Briony Kidd as a showcase and forum for horror directed by women. My coverage of the festival can be found on the RealTime Arts website, but I’ve decided to post my full interview with Briony Kidd here so that her insightful views on women in horror and the Australian film industry can be shared.

There’s a great sense of community at Stranger With My Face. What outcomes does the networking at the festival foster for women’s filmmaking, do you think?

“Horror” has been (and continues to be for some) a dirty word in the Australian film industry, so you can feel a bit isolated if that’s what you’re into. Add to that being female in a very male-dominated genre, and the effect is compounded. On the most basic level, it’s just nice to hang out with like-minded people. There’s also an opportunity to support each other’s work and develop relationships. A number of creative collaborations have developed out of the festival, which tells us we’re on the right track.

For the benefit of readers who may not be familiar with Women in Horror Month and the activities which spring from it, could you give us a bit of background on what motivated you and Rebecca to launch the festival?

Women in Horror Month is every February and was started in 2010 by Hannah Neurotica, who also writes a feminist zine called Ax Wound. I became aware of it when a short film of mine was selected to be part of the Viscera Film Festival, which was a festival based in Los Angeles run by Heidi Honeycutt and Shannon Lark. The two events worked very closely together. I think Viscera was the first fest to focus specifically on women-directed horror and it was great because, apart from just screening films, they would tour their program by allowing other festivals, or anyone who wanted to actually, to look at their catalogue of films online and curate their own selection.

That’s all I wanted to do initially in 2012, just screen some of the Viscera shorts as a Women in Horror Month event in Hobart. But there were other films that I wanted to include as well, and then we wanted to have talks and a script comp, and it very quickly became its own thing. So we ran with it and called it Stranger With My Face Horror Film Festival (after the Lois Duncan YA novel) because the kind of horror I’m most interested in as the programmer of the festival concerns the ‘horror within’ rather than your more straightforward external threat.

Stranger With My Face 2014 continues on into the night at Salamanca Arts Centre

What are you looking for when you search for films for Stranger With My Face?

I’m looking for films that have something to say. There’s an assumption that genre is mainly escapism but, to me, there’s so much scope in horror to be provocative or extreme or personal or original, so why wouldn’t you take advantage of that? The films should also be well made, of course.

What (apart from all of it!) were some highlights of this year’s festival for you?

It was a big deal to me to get Ann Turner and Rebecca Smart down for the screening of Celia because I think it’s an extraordinary film. I was happy that the audience seemed to agree. There was a moment afterwards at the Brisbane, listening to The Night Terrors with Ann and Rebecca next to me nattering away having a catch-up, that struck me as being quite surreal. In the best possible way.

Another highlight was seeing what the Tasploitation Challenge filmmakers came up with this year, particularly some of the women-directed films where the directors were also performers and threw themselves into it fearlessly. The film that won was made by a team of a father and his two young daughters. It’s inspiring to see what people come up with when they have ‘permission’ to cut loose.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas talks women in horror at the Mary Shelley Symposium

Was this year’s Mary Shelley Symposium [the festival’s series of talks on genre and gender] programmed after the films were selected? If so, was its content tailored to complement the films on offer?

The two are programmed side by side, but I wanted it to feel like they were riffing off each other in various ways. For example, Emily Bullock talked about Tasmanian Gothic and The Tale of Ruby Rose and we screened the short film Little Lamb, which is a new example of Tasmanian Gothic and the director’s mentor in making it was Roger Scholes, the director of Ruby Rose. I also realised there was a fairytale element to a lot of the films I was considering for the program, so adopted that as an informal theme across the program.

Are there any aspects of this year that will affect the way you approach next year’s festival program (if it’s not too early to make that kind of call)?

Next year will consolidate the focus on bringing in guest filmmakers. I’d like to give them even more opportunities to interact, both with each other and with artists from other disciplines who are in the audience or who are also part of the program. Perhaps we could instigate some kind of creative lab or a joint project.

In contrast to last year, there seemed to be a shift in 2014 towards feature films from Australasia. Is this something you’re interested in building on?

We have made, and continue to make, outstanding genre films in this country… and I think that point gets a bit lost in all the doom and gloom about distribution. The Australian component of the festival has certainly grown from the first year of the festival and it actually seems like there’s a lot more to choose from now, which is encouraging. We haven’t really had any New Zealand filmmakers involved with the festival and that’s something I’d love to rectify for next year.

Briony Kidd in conversation with Australian short filmmakers Heidi Lee Douglas (Little Lamb, 2014) and Caitlin Koller (Maid of Horror, 2013)

Finally, the question I always pose, just out of my own interest, to Australian horror filmmakers: do you think it’s difficult to get horror films funded, distributed and seen in this country?

It’s very difficult to get any kind of films funded, distributed and seen in this country, but horror in particular has a troubled reputation. It’s been said that it “doesn’t work” at the local box office, but I’d argue most Australian films don’t work at the local box office and it’s for reasons that are complicated and are not a straightforward measure of quality or of audience’s actual interest in the content or genre.

The up side is that it’s a time of transition and some clever genre filmmaker is probably just about to solve the problem of how to get their content to a local audience quickly and efficiently and in a way that will be exciting for everyone and even (gasp) modestly profitable. And of course, there’s a whole world out there that’s hungry for new ideas, and there’s nothing wrong with looking to the international market if that’s where your audience is. We probably need the funding agencies to recognise that more, that box office in Australia is no longer the only way to have a successful or reputable career.

My RealTime Arts article on the 2014 Stranger With My Face Horror Film Festival is here.

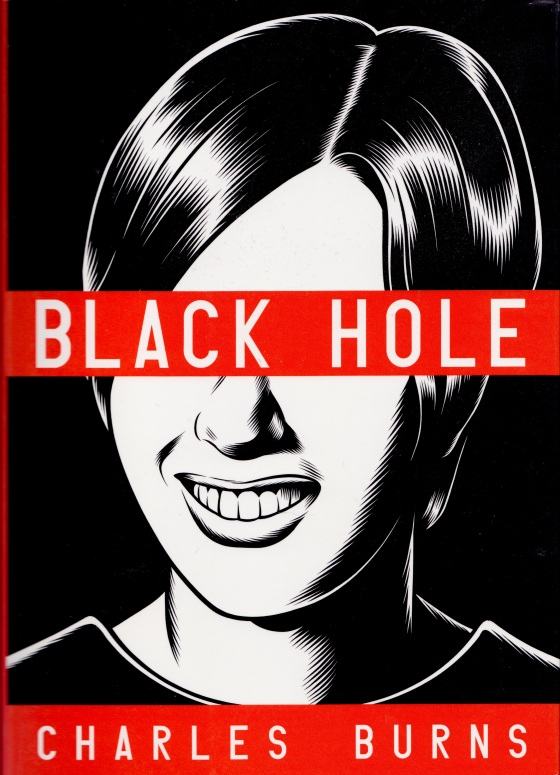

Charles Burns’ graphic novel Black Hole sucks you in, true to its title, with irresistible momentum. Taking place in mid-1970s Seattle, the backdrop to Burns’ own adolescence, it chronicles the impact of a curious sexually transmitted disease that causes its teenage sufferers to physically mutate in a variety of wild ways. The story zeros in on two personable characters: easy-going yet sensitive Keith, and Chris, the girl he’s besotted with, who is both popular and kind.

Charles Burns’ graphic novel Black Hole sucks you in, true to its title, with irresistible momentum. Taking place in mid-1970s Seattle, the backdrop to Burns’ own adolescence, it chronicles the impact of a curious sexually transmitted disease that causes its teenage sufferers to physically mutate in a variety of wild ways. The story zeros in on two personable characters: easy-going yet sensitive Keith, and Chris, the girl he’s besotted with, who is both popular and kind. Burns’ chosen medium is scratchboard, a drawing surface developed in the 19th century and popularised by illustrators in the mid-20th century. Consisting of a layer of white china clay on board, coated with black ink that can be scratched into with customised scribes, it was an expedient way for illustrators and publishers to emulate the dramatic black and white contrast of wood-cut prints. Burns is a dizzying master of this form. In his hands, darkness becomes luminous. His nightscapes are shiny and almost wet-looking, like phosphorescence in a black sea.

Burns’ chosen medium is scratchboard, a drawing surface developed in the 19th century and popularised by illustrators in the mid-20th century. Consisting of a layer of white china clay on board, coated with black ink that can be scratched into with customised scribes, it was an expedient way for illustrators and publishers to emulate the dramatic black and white contrast of wood-cut prints. Burns is a dizzying master of this form. In his hands, darkness becomes luminous. His nightscapes are shiny and almost wet-looking, like phosphorescence in a black sea. If Black Hole’s dazzling fragments can be unified by any one theme, it’s the destructive potential of sex, love and desire, which pulls Chris and Keith into increasingly murky and desperate territory. Most obviously, sex can make you sick, monstrous and ostracised; more insidiously, thwarted love festers into self-harm, obsession and violence. In Black Hole the heightened social stakes of adolescence take on grotesque proportions in the hidden, anarchic space of the woods.

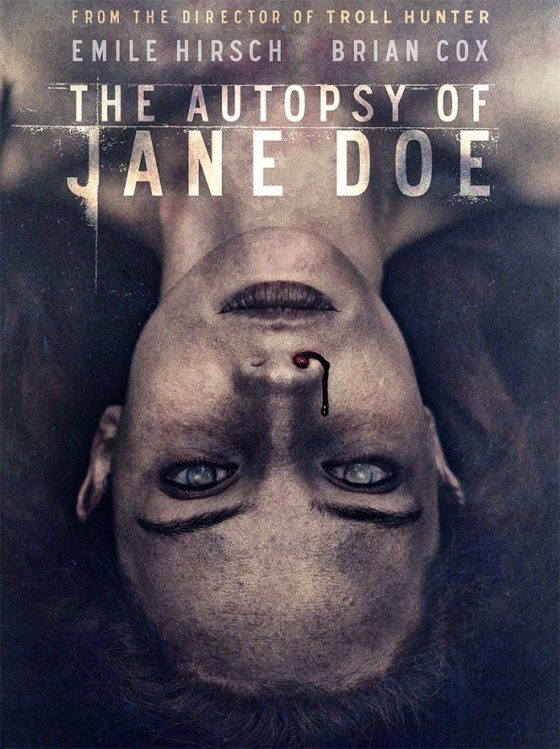

If Black Hole’s dazzling fragments can be unified by any one theme, it’s the destructive potential of sex, love and desire, which pulls Chris and Keith into increasingly murky and desperate territory. Most obviously, sex can make you sick, monstrous and ostracised; more insidiously, thwarted love festers into self-harm, obsession and violence. In Black Hole the heightened social stakes of adolescence take on grotesque proportions in the hidden, anarchic space of the woods. As The Autopsy of Jane Doe unfolded, I couldn’t help thinking of Kristy Guevara-Flanagan’s short film, What Happened to Her (USA, 2016). In a

As The Autopsy of Jane Doe unfolded, I couldn’t help thinking of Kristy Guevara-Flanagan’s short film, What Happened to Her (USA, 2016). In a